Black Bough Poetry

Book of the Month

April 2025

Jen Feroze’s ‘A Dress with Deep Pockets’ was a joint winner in the Poetry Business International Book & Pamphlet Prize, judged by Jane Clarke. It’s a bargain at £6 for 20 poems, which is arguably a perfect length for a poetry publication (after all, great poems get lost in hefty collections). It’s worth mentioning the burgundy cover and cream paper which show off some very polished and surprising poems. After winning such a prestigious prize, a good, hard look at this is needed to extract its magic ingredients.

Jen Feroze’s work often takes as its focus the nuances of female friendships, as seen in previous publications The Colour of Hope and Tiny Bright Thorns. ‘A Dress with Deep Pockets’ presents a range of individual women, including a wild, untamed friend in the first poem ‘Hare Girl’, who is “sleet, fleet, disappearing into trees”, prowling through nature and another, a newly single friend, prowling around a museum who,

[…] talks about the paintings of women

Weeping at the dark edge of the water,

Corsets of pink silk where tiny acrobats

Swing on tightened ribs

One of the most entertaining poems in this publication is one about a formidable, larger-than-life teacher “beefy like an operatic fable” with a voice “like a Christmas cake” striding around a school; In ‘Boxing Day Swimmers’ women babble and wobble at the sea’s edge in a comic poem where a mother is described as a “mournful clockwork woodpigeon” (genius!); elsewhere, friends howl in an office and another poem is chaotic with the frenetic activity of women in a commune. Jen Feroze knows how to nail a quirky description and uses this technique quite sparingly to maximise the effect when it is deployed.

These are poems that also stop at still, thoughtful moments of friendship – a balcony in France with drunk friends, smoking and contemplating the regret of a break in friendship (not being there for someone), the camaraderie of garden parties and sharing food – notably a lot of dipping crusts in oil and enjoying cake and cream (I want to go to one of Jen Feroze’s parties please or at least buy her poetry cookbook). Cholesterol tablets advised!

The strengths of this pamphlet are pretty evident from the off. Firstly, it reaches well outside of the poetry community, avoiding too much of the wilful abstraction, or crazed navel-gazing many poets get lost in. The emotional cocktail, or smorgasbord, of nostalgia, wistfulness, yearning and fear is relatable and not too difficult to break down. I can imagine this being enjoyed at book clubs and shared between friends - a tight, accessible, relevant poetics, in tune not only with the market but the readers' hearts.

Feroze could give anyone a lesson in tight, economical phrasing, not overdoing it and peppering in witty, poetic lines – somewhere on the platter between Liz Berry, Caroline Bird and the smoked salmon. This is a pamphlet very much informed by contemporary poetry but has its own soul, not hanging off anyone’s tray of canapes. From punching the cold of winter “right in the centre of its stupid face” to women punching Rugby players or teachers throwing board rubbers, any sentimentality is frequently, and rightly, disrupted. Any platonic lovefest between friends is disrupted by occasional outbreaks of chaos.

Perhaps the most memorable poem is one where the speaker, a mother, contemplates inviting her grown-up daughter round for dinner and what that might look like. The prospect is, once again, salivating, with offerings of "oven chips […], Prosciutto and fresh peaches”. A poem laced with a sense of future loss and hope.

Jostling with this poem for attention is the arguably more impressive write (in regards to scale ) ‘Gorge’, where the writer takes us to her origins near Cheddar Gorge, taking us across a panoramic, deep-time landscape, zooming in on a tragic circumstance involving a friend and an array of characters, including a teacher and the ancient, mesolithic Cheddar man, in stark contrast to where her and her friends are now, lured to the bright lights of the city and its glassy structures. This poem is a sharp cut-away from the intimacy of friendships and the interiors of garden parties and kitchens and more communal spaces - a breadstick with balsamic vinegar of a poem, one that is particularly skillful and shows Feroze as a deft writer of place - a direction to look at in future?

As they have always done, the cliffs stand silent, a knowing smile

carved from water into the landscape of so many childhoods. Only once

we left, did I see how we’d been shaped, hot as blown glass; forged, gorge-made.

Jen Feroze's 'A Dress with Deep Pockets' is genuinely delightful, tasty even, in its twists and turns between wistfulness and joy. A cracking present for the literary buff or the most casual of readers and not, exclusively, of interest to women, despite its target audience. It will also leave you wanting to go to Waitrose or M&S for the Finest ranges. JustEat or Deliveroo simply wouldn't do.

Reviewed by Matthew M C Smith, author of The Keeper of Aeons.

Black Bough Poetry

Book of the Month

February/ March 2025

The Black Bough book of the month for February/ March 2025 is Alison Lock’s Thrift, published by Palewell Press (2024).

Alison Lock is a widely-published poet, based in North Wales, having been born in Devon and lived in West Yorkshire for decades.

Alison has been featured on BBC Radio in the past and her work can be read in publications, such as Anthropocene, Arc Magazine, Atrium, Blyth Spirit, Caduceus, Contemporary Haibun, Daily Haiku, Dawntreader, Empty House Press, Ethelzine, Feral Literary Magazine and Indigo Dreams Press anthology For the Silent, to name but a few.

With Black Bough, I’ve published Alison’s work, which I always find imaginative, often striking, always with some kind of emotional undertow, whether this is fear over the loss of species or a kind of wild joy as a witness.

The marketing information describes the work in the following way:

The collection’s poems are grouped into three sections: Rue, Thrift and Sage – herbal names that lead readers on a spiritual journey from despair through learning to be more frugal and sustainable to a new wisdom and potentially more hopeful future.

I'm sometimes wary of very direct, political poetry because sometimes the poetry itself suffers when it becomes didactic. I prefer eco and environmental writing when it awakens the sentient side of the reader or listener, promotes a sense of awe at the interconnectedness of everything and immerses us into many different micro worlds, helping us to completely escape our lives in concrete, steel and wood structures, within grids of cities, towns, villages, ever-tethered to responsibilities and our crucial role as consumers and servants of a hyper-capitalist world. It is this sense of freedom that we experience on Alison Lock’s experiential poems which take us not only out of this oppression but outside the self.

In the first poem ‘Dawn’, with its perfect shape, we are taken to the “calm /before the tally time/ when clocks enumerate their/ hourly psalms, barometers preponderate […] Small comforts / gained from dying flames, a floorboard’s off-beat creak”. There’s an interplay of sound and image that takes us immediately and memorably to that place – we are within the environment of the poem, feeling, witnessing, listening in. I liked the ‘yogic stretch of the dog’ – a witty touch, and one example of where this pretty serious poet has a lighter touch. A strong start, what next?

‘The Monarch of Mabon’, a butterfly poem celebrating arrival of the ‘Monarch’, takes us to “fields [that] reflect the cumulous pattern/ of cloud on the blade-cut/ silvered soil – our second harvest./ All is still. On the road/ rolls neither car nor tractor,/ but there is movement/ in the hedgerow, a butterfly lands. In this poem, we are incrementally introduced to The Monarch, with its ‘Black-veined wings [that[ delineate her shape as she grazes on the milkweed’. I appreciated the pacing and the detail. Neither undercooked or undercooked. An extract of the poem is below:

Another poem ‘Melting Iceberg’ sees the poet going from the small world of hedgerows and fields to a bigger poem, with its climate crisis theme, the melting of icebergs. Preceding the haunting final image, the sequence of images – the fly in the eye, the eerie sounds of the iceberg and the poetic evocation of extinct animals is a figurative, indirect approach to presenting the climate crisis – no drum beating – just sheer poignancy – showing rather than telling.

The poem ‘Winscar’ would probably get a vote from some readers as the best poem. The poet presents a valley with tumble-down farmhouse, a valley drowned by the waters so it has become an inland sea. Under the waves, life is teeming and Canadian geese migrate temporarily. With rising waters, habitats evolve but there is an impending sense of doom, for humanity at least. ‘The Elders of Laddow Rocks’ continues on the theme of the ancient valley and there’s a touch of Ted Hughes’s ‘Remain of Elmet’ – at least in the austere atmosphere of a northern, gritstone valley, where humans are insignificant.

This collection of nature poems is a thoughtful and sensitive read by a strong, yet understated poetic voice. Get this book!

Review by Matthew M C Smith, editor of Black Bough and author of The Keeper of Aeons.

Black Bough Poetry

Book of the Month

January 2025

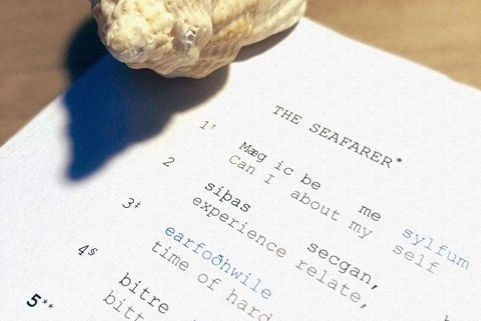

‘Cold to my cage,

my feet unfound, these bones a scaffold of frost;

then the starvation inside’

(Matthew Hollis)

Coldly afflicted,

My feet were by frost benumbed.

Chill its chains are; chafing sighs

Hew my heart round and hunger begot

Mere-weary mood.

(Ezra Pound)

The Seafarer, by Matthew Hollis and Norman McBeath, Hazel Press, November 2024. Review by Matthew M. C. Smith. Click here for more info

The Black Bough book of the month for January 2025 is Matthew Hollis’s pamphlet, 'The Seafarer' (Hazel Press), a new translation of the canonical, epic poem which is, in its inception, a monologue of a prophet-voyager, and one included in most, if not all, anthologies of Anglo-Saxon poetry. A daunting prospect for any writer to take on given its status.

The cover, which features sea-spray against black in an original photograph by Norman McBeath, gives us a salty foretaste of what is to come. The beginning of the text includes an extract from the original Anglo Saxon poem, then the poet’s own translation of this ancient poem, followed by a gallery of fourteen of McBeath's photographs specially prepared for this edition. Most of these photos are elemental, capturing the bitterness of the wind and waves - a smart pairing by Hazel Press.

I was expecting something of Ezra Pound’s version of the poem (from 1911) with the modernist’s insistent rhythms and strong alliterative meter. Hollis wrote extensively about Pound’s influence on Eliot’s The Waste Land in the Faber published The Waste Land: Biography of a Poem (2022) (this was Black Bough book of the month earlier this year Click here for more info) and the American’s version is one readers and academics often go to, with its notoriety as a particularly creative and dramatic translation. By the way, if you haven’t heard Pound reading his translation of the poem, please do. You can imagine the American poet with a Viking helmet, standing at the prow of a long ship, heading into a Baltic storm. Highly memorable, highly eccentric. Read other versions too!

Hollis makes it new in his own way. No long ship, no reconstruction of a helmet – more of the glow of the fireside with the bard whispering rhythmical verse as the shadows of the old world dance around storyteller and the listeners. If you’ve heard the London-based poet and biographer read before, it’s worth mentioning that there is a gentleness and sensitivity to his voice (both poetic and in his speaking) that recalls the best elements of the English tradition – Hardy, Edward Thomas, something of Eliot. In his recent Earth House (Bloodaxe Poems), we are taken across land, city and seascapes in a lyrical tour de force, brought to life when the poet reads this with inflection and emotion, the personal aspects of the writing becoming more obvious in the listening. In this work, we are plunged into the icy cold of the dark ages.

Hollis’s version of 'The Seafarer' feels like a fresh, bracing, windswept embrace, one geared for an era where Peter Jackson’s Hobbit and Lord of the Rings films have reintroduced the Norse-inspired epic to the masses. There is a strong focus on the alliterative and sibilant patterning and the mid-line breaks of the original

‘watchful at prow, my keel-hand

shaking in the spill; driven too much

towards rocks. Cold to my cage,’

‘Swan song, sometimes, a whooper’s wail

‘but a hummer-sung sea, its weld of waves’

but this verse patterning is not slavishly kept to and contrast is effectively employed as the poetry opens out and breathes in flourishes, let out of the tighter, original constraints.

‘COME, LEAN IN for this song of myself.

Bear with me these tides of telling’

‘Whoever settles

their days on land will never know the wintered waste,

the sheer alone, the friendless furrow,

cloaks of icicle, hail flown – ’

Note Pound’s version, dramatic, if a little stilted and Victorian:

May I for my own self song’s truth reckon,

Journey’s jargon, how I in harsh days

Hardship endured oft.

In immersing us into the worlds of Beowulf, Tolkien and the epic tales of Snorri Sturluson, Hollis’s eye scans across black and white landscapes from mead-halls to the ‘cradle of towns’ in visions obscured by snow, with barren backdrops in the freeze of winter. It’s interesting that explicit references to God and Christianity are taken out but unsurprising given that scholarship for a long time has doubted lines considered to be put in afterwards, the poem being seen as Christianised, after its original iterations. This version is truly ecumenical, worldly in the broadest sense, untethered to any particularly religious traditions, meaning that is has the potential to speak to all, whatever faith background or secular.

The emotive, reflective points of the texts are expertly rendered by Hollis – if the austere Anglo-Saxon world is very much retained, there is a fragility and softness in the speaker’s delivery, a difference from the alternating melodrama and bombast of Pound. I couldn’t help thinking of Whitman, although this, admittedly, is a very loose comparison:

‘And so

how is it that the heart pulls harder:

draws me deeper onto towering seas;

commands me out to salt-break;

to go further in as I go further out;

guided by this spirit-guide, this unhoused host –

[…]

The days

fall through my fingers, the shore

recedes from sight. Neither kings

nor caesars, nor the gold-giving lords

remain of times before, when

they moved with glory and unknown.

This is a graceful translation, one that displays plenty of respect and humility in its interpretation of the original – there’s nothing avant-garde or overly-experimental about it (thankfully!). In the poet’s own words:

‘Humility is a gift; grace of light is a gift.

A measured heart is stable. And so with trust comes might’

Hollis’s 'The Seafarer' is a version for a new generation, one that hearkens back to the atmosphere of the old worlds of ice and snow that it navigates, whilst retaining the raw emotion and the prophetic power of the original. Get it and prepare to be mesmerised.

Review by Dr. Matthew M. C. Smith, author of The Keeper of Aeons and editor of Black Bough Poetry. January 2025.

Matthew Hollis reads a short extract from the original at an exclusive Black Bough reading, Dec 2024.

Translating the Seafarer: An interview with Matthew Hollis

Matthew Hollis reads a short extract from his translation at the exclusive Black Bough reading, Dec 2024.

Matthew M. C. Smith interviews Matthew Hollis about the process of translating 'The Seafarer'.

MS - Your translation of 'The Seafarer' seems to focus on both universal, timeless and the most contemporary concerns: the vanity and transience of human power, the certain doom we all face and, above all, the might of nature. Is this how you view the text and how did you navigate these themes?

MH - I think you’ve put it very well: a tireless connection of ancient and modern, and the questions that pertain to both. Socrates asked us to live an examined life, and I think 'The Seafarer' does the same. The poem asks us to consider the choices we make – most obviously whether to live a life on land or on water, of course, but more deeply, whether to choose a life of belonging or exile, one to which we contribute or withdraw; one of fixture or of journey, one of acceptance or of enquiry. And it encourages to be in tune with our response, whatever that be: environmentally, certainly, in its exquisite sense of the balance of the elements and the natural world that the Anglo-Saxons were so much more aware of than us – but also spiritually. It asks us What do we value in life? And, How should we live it, if – as the poem suggests – we may not be able to take our achievements with us? Those questions mattered to the ancients as well as to the Anglo-Saxons, and they are surely no less critical today at a moment when our ecosphere is on the precipice, and our belief in social and political responses are tested to the limit. The poem seems to be asking, What kind of living is sustainable, and, What are we willing to do to achieve it? And that right there is the universal and particular in one moment, and therefore poetry at its most valuable.

MS - Why did you choose to translate 'The Seafarer'? What translations did you look at and how did you respond or react to them?

MH - I have wanted to tackle 'The Seafarer' for twenty years, but have been waiting until I felt I had enough life-experience of my own to undertake it – as well as acquiring the literary tools. I read everything that had gone before, for we can learn so much from what our ancestors have achieved, and see how they rose or fell to the challenge of the many difficulties in the poem. Ezra Pound's great, flamboyant translation of 1911 remains a landmark today, not least as a kind of performance-piece of what at the time was a little-known commodity. And that’s because one of the oddities of 'The Seafarer' is that although it was most likely composed in Old English in the 900s (we say probably as we don’t know for sure), it wasn’t until the 1800s that it was first rendered into Modern English, and only then by and for the scholarly community. Pound’s version – by a poet for poets – was the first to enter the common place of poetry and the first to popularise the poem, with its busy-buzzy audio waves and dramatic telling. It’s not to everyone's taste today, but let’s think about the importance of that breakthrough for a moment: namely that 900 years after its composition, the poem for the first time finds its place in the new language, as though a long, lost wreck has been recovered from beneath the waves, rescued for a modern audience to encounter. The poem had been known in English for seventy years when Pound published, but it hadn’t yet reached its audience. Since then it’s been brilliantly handled by later translators, Michael Alexander and Richard Hamer among them, but Pound somehow got everything going, as was his want and his gift in life – this American renegade turning London on its literary head in order to point out the importance to us of what was right beneath our feet.

MS - Which parts of your version do you like the most and which parts, if any, did you struggle with?

MH - All of the version was a struggle; but then, all of writing poetry is a struggle for me. Here, at least the difference in the kind of struggles between working a translation and an original poem is a tangible one, as it involves a contrasting sense of responsibility. When writing for yourself your duty is very clearly to your poem; but a translation is not your poem in the same way – and in an anonymous case such as this, it is a poem that belongs to us all. And by ‘us' I don’t mean 'the English’ old or new, I mean everyone on these remarkable islands, whatever your language or background. And if you believe that, then the responsibility and the struggle of transmitting this is going to be considerable. But there is a pleasure and reward in trying to assemble the pieces. Are there two speakers in this poem or one? What kind of bird is the Seafarer hearing? What is it that they are trying to communicate to us about life? What should we do about the Christianised adjunct of an ending? This latter is such a challenge that some translators (Pound included) have simply lopped off that later part of the poem. My hope has been not to make removals, only to have admitted other readings of a more figurative kind, where the numinous and the secular might equally be granted: Christian, certainly, which was undoubtedly the scribe's motivation, but also the thought that another kind of spirit music can reside within the poem – a guide to the miraculous attunement that I think the Seafarer sought to make with the world.

MS - When you read the poem at our online reading in December, you had listeners completely absorbed. What is it about this poem that has that effect on the listener and what is your approach in the telling of it? What would you like readers and listeners to get out of the poem?

I'm very glad if hearing the poem was enjoyable, and I’ve just recorded it for someone for whom reading the printed text posed a difficulty (the recording is on my author site if anyone wishes a listen). But really it's the song, not the singer, that carries this poem through. For it’s an incantation, a tale made for telling, to be given and received in company, to be societal. And that matters because of the messages that it carries, in words that bear so much worldly knowledge, so much lived experience and so much prophecy. And that’s not all they carry, but something else besides: love, dammit, which might seem like an unlikely word to introduce into a 10th-century sea-quest, but you can sense it there in between the salt-encrusted lines of the old poem. It’s the prize sought amid the imminent and elemental dangers of the poem’s world: something to capture and cherish, something to hold on to, a foothold, a grounding against an otherwise endless and empty sea. Love of the great complexity of life, acceptance of its pain, humility in the face of its rewards, a betrothal to the power of nature, self-reliance, other people, faith: whatever each of us believes to be a higher power. It asks us to think about the deep and lasting value of these moments, and about what we are prepared to do in order to experience and preserve them. It urges us all to wake up to our world.

'Whoever settles

their days on land will never know the wintered waste,

the sheer alone, the friendless furrow,

cloaks of icicle, hail flown'